The Full Story

Our History

THE ROYAL GOLF CLUB STORY

The Beginning

The Royal Golf Club

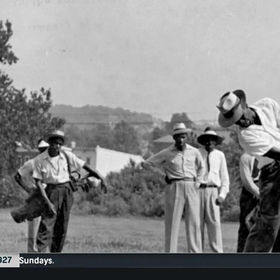

Prominent black Washingtonians founded the city's first African American golf club, the Riverside Golf Club, in 1924. In 1925, the all-Black Riverside Golf Club was organized to promote play on the municipally owned Lincoln Memorial Golf Course in Washington, DC, which opened on June 8, 1924. Some members split off from this club six months after its formation to organize the Citizens Golf Club, which later changed its name in 1927 to the Capital City Golf Club.

From the opening of the Lincoln Memorial course until today, African American golf clubs grew and flourished in Washington, DC. They were the organizing force behind both protests against segregation and home-grown golf champions and tournaments. As the country was establishing Jim Crow, white organizations were routinely excluding blacks from participation in various professional sports, including those in which blacks had been prominent. To counter this, African Americans established alternative institutions. In golf, it was the UGA, the United Golfers Association, in 1926.

Blacks in Washington, DC were allowed to lay at a nine-hole layout in the area between the Lincoln Memorial and the Old Naval Hospital at 24th Street and Constitution Avenue, NW. The greens were round, about twenty feet in diameter and covered in sand. Even the average player could drive all but three of the holes with irons. This course had been built due to the efforts of a group, the Capitol City Golf Club. With the opening of the course for daily play more people became attracted to the game. Some of these were from the Caddy rank, and others took the game up for recreation. The Capitol City Golf Club tried to establish another golf course and country club in the area, but the project never got off the ground, so those plans seemed to fade.

From this group there were those who felt that widening the scope of play, improvement of the facilities and the proper sponsorship of tournaments were definite needs. So a meeting was called and interested golfers were invited to meet for the purpose of forming a club. After some informal discussion, it was decided to organize and a committee was established in the year of 1933 to draft a constitution and thus the Royal Golf was named. The club's membership at the beginning was very small and consisted of quite a number of professional people-doctors, lawyers and notable members of the Washington, DC area. Later however, this image changed very drastically when they became better organized and started promoting different golfing events. From this point on, the membership grew larger and more diversified until it became the club that represented golfers from every walk of life.

With a burgeoning number of African American golfers in the city, Capital City/Royal Golf Club began advocating for expanding facilities and requested that the federal government (which operated all five golf course in the city limits) construct a new 18-hole course for Blacks to play. In 1927, John Langford, a prominent black architect in the city, petitioned the federal government to build the course on the new Anacostia Park. Over the next several years, African American golfers in the city and surrounding areas held rallies, attended hearings, wrote letters, and lobbied Congress and executive branch officials to build the new course in Anacostia Park.

In 1934, government officials et with the Black golfing community, including members of the Royal Golf Club, and agreed to build the course in Anacostia Park. The first nine holes of Langston Golf Course were built in 1939. When it opened, the course was not in good shape and some of the greens lacked grass. The inadequate facilities at Langston led many black golfers to continue to lobby for expansion of the course. African Americans attempted to play golf at the all-white East Potomac Park Golf course, Rock Creek Park Golf Course, and other all-white courses, but were usually prevented from doing so. Black golfers continued to lobby, rally, and testify in favor of an additional nine holes at Langston, until the back 9 was constructed and opened in 1955.

Whatever is past is by-gone, and very soon becomes history, and according to certain trends of modern thinking should bear little or no relationship to the present. Unlike our European neighbors, who, seem to go to great lengths to honor, protect and preserve many of their historical Shrines, Treasures and Artifacts, while a good number of Americans seek to destroy every vestige of our past, perhaps, for fear to remind them of a more primitive age. Be this as it many, there is still plenty of evidence to indicate that many of our institutions and establishments of today were largely built on the foundations that were created by those who precede us. It, therefore, affords us great pleasure to bring attention some of the past, as well as the present history of the Royal Golf Club.

Narrated by Jeffrey Wright who tells the story of how Black golfers in Washington, DC carved out their own space.

The first African-American women's golf club in the U.S. also started in Washington, DC. In August 1936 Helen Webb-Harris invited twelve women to her house to discuss starting a women's golf club. In 1937, they became the founding members of the club known as the Wake Robin Golf Club. Many were wives of the Royal Golf Club who were tired of staying home on the weekends while their husbands played golf. Although the two clubs had very similar goals and purposes, for them golf was more than a game, and their goals were to help women and youth learn about golf, play in tournaments, and become champions. The Wake Robin Golf Club also aimed to fight for the integration of golf course and programs. They have produced more champions than any other women's golf club.

The WAKE-ROBIN GOLF CLUB

Sister organization to the Royal Golf Club

GOLF & CIVIL RIGHTS in Washington, DC

The most famous stages of civil rights activism include schools, churches, and public transportation – but golf courses?

In Washington, DC, golf was one of the many fronts where African Americans fought for equal access to public facilities in the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. From community building to lobbying to direct action in 1941, their activism influenced integration in the nation's capital city and parks.

By the turn of the 20th century, the District of Columbia had the largest and most prosperous African American population in the country. Yet schools, parks, playgrounds, and other public facilities were segregated.

After World War I, when thousands of black veterans returned from the front, they found that inequality was worsening at home. As tensions rose in the summer of 1919, more than 20 race riots erupted across American cities, including Southwest Washington. In DC, rioting continued for three nights, and 2,000 federal troops intervened to stop it. These riots showed there could be a "strong, organized, and armed black resistance, foreshadowing the civil rights struggles later in the century," according to a Washington Post retrospective. This period of injustice and unrest is the prologue of the story of how golf became a civil rights issue.

THE GOLF INTEGRATION MOVEMENT

The Royal Golf & Wake-Robin Clubs & the Integration Movement

In the 1940's, members of the Royal and Wake Robin golf clubs brought the fight for equal access to the public golf courses. Their actions were among the earliest to spark a large and growing movement against Jim Crow segregation in the 1940s and 1950s. Filing a lawsuit and waiting for the courts to force integration was the expected strategy at the time. Washington, DC's black golf clubs decided on a different course of action. On June 29, 1941, Asa Williams, George Williams and Cecil R. Shamwell arrived at the East Potomac Golf Course to play a round of 18 holes. These African American golfers were members of the Royal Golf Club. They were told that "colored persons are not allowed to play at the East Potomac Course and began to play, accompanied by park police officers.

Looking forward to inviting the United Golfers Association to bring the national tournament to Washington, DC in 1942, the Royal Golf Club, together with its sister organization--Wake Robin Golf Club, launched a major effort in attempting to bring about integration of these golf courses. Some of the efforts were not received very graciously by many of the whites, who frequently played these courses. Just about every trick in the book was used to prevent this from happening, including a bit of violence.

The break came when the National Capitol Parks, a part of the Interior Department, which at the tie was headed by Secretary Harold Ickes. He authorized the use of the Anacostia Golf Course to stage the U.G.A. National tournament. With this great undertaking behind them, the integration program became a bit smoother. Within the next two years, all of the public courses were being used. This did not end the hostility. Although on several occasions open resentment was encountered, no further incidents took place (at least that were recorded) but ugly remarks were heard quite often.

The Royal Golf Club sponsored an annual Amateur Tournament and set the pattern for golf activities at the golf course. In addition, the club became the spearhead to increase golfing activities by pointing out the inadequacies of the Lincoln Memorial Course. After continuous effort, a tentative layout on the present site of Langston was offered. However, considerably more pressure was necessary before the Langston Golf Course was opened.

After the official desegregation of public golf courses, African Americans still faced intimidation when they tried to play. A couple of weeks later, a fight broke out at the East Potomac Park Golf Course when African American golfers sought shelter from a torrential rainstorm in the field house.

In September, the Afro-American wrote that "White hoodlums, resenting the appearance of colored players on the hitherto lily-white courses, have been making things uncomfortable for adventuresome golfers; effecting malicious little triflings [sic], like filling carburetors with sand, deflating tires, removing spark plugs and other such things while the owners were out on the course."

A year later, in July 1942 at the Anacostia Golf Course, women from the Wake Robin Golf Club were harassed by a white crowd, who reportedly picked up the golfers’ balls to prevent them from playing and drove them from the course with sticks, stones, and abusive language.

One way African American golfers hoped to show their right to play was to hold the 1942 United Golfers Association (UGA) tournament, known as the "Negro National Open," on one of Washington, DC's, public courses. Dr. Edgar Brown wanted to "fashion a decree from the Department of the Interior...providing one of the swank courses, now used by white people, for the event."

Under pressure from white organizations, the UGA canceled the tournament. The Wake Robin and Royal Golf Clubs were undeterred.

The Langston Golf Course

The Royal Golf Club and the Langston Golf Course have been so closely associated over the years that it is somewhat difficult to say very much about one, without mentioning the other.

In 1938, the Royals and Wake-Robin Golf Clubs pushed the process of desegregating the public golf courses in Washington, DC by petitioning the Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. Even though the Langston Golf Course opened in 1939, making it the second course in Washington that people of color were allowed to play, the Royals and Wake-Robin continued to petition the Secretary until public courses were desegregated in 1941. On June 30, 1941, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes issued an order to open the golf course to all players. He also insisted that African Americans could buy tickets to any of Washington, DC's, traditionally white public golf courses, writing:

"I can see no reason why Negroes should not be permitted to play on the golf course. They are taxpayers, they are citizens, and they have a right to play golf on public courses on the same basis as whites."

After the official desegregation of public golf courses, African Americans still faced intimidation when they tried to play. A couple of weeks later, a fight broke out at the East Potomac Park Golf Course when African American golfers sought shelter from a torrential rainstorm in the field house.

In September, the Afro-American wrote that "White hoodlums, resenting the appearance of colored players on the hitherto lily-white courses, have been making things uncomfortable for adventuresome golfers; effecting malicious little triflngs [sic], like filling carburetors with sand, deflating tires, removing spark plugs and other such things while the owners were out on the course."

A year later, in July 1942 at the Anacostia Golf Course, women from the Wake Robin Golf Club were harassed by a white crowd, who reportedly picked up the golfers’ balls to prevent them from playing and drove them from the course with sticks, stones, and abusive language.

One way African American golfers hoped to show their right to play was to hold the 1942 United Golfers Association (UGA) tournament, known as the "Negro National Open," on one of Washington, DC's, public courses. Dr. Edgar Brown wanted to "fashion a decree from the Department of the Interior...providing one of the swank courses, now used by white people, for the event."

Under pressure from white organizations, the UGA canceled the tournament. The Royals and Wake-Robin Golf Clubs were undeterred. A letter dated December 3, 1943, drafted by members of the Royal Golf Club to the Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Harold Ickes, was accompanied by a map showing a proposed layout for an extension to Langston Golf Course that had been under study by the Department of Interior. In June of 1950, the second nine holes was opened at Langston, an accomplishment of the efforts of the Royals and Wake-Robin Golf Clubs and many others from golfing Associations in the city who waged quite a battle in regard to the project. Letters here & 1949 Langston Golf Course Map

Over the years, it also became a see-and-be-seen destination. Heavyweight champion Joe Louis played an amateur tournament at Langston in 1940, drawing 2,000 fans. Lifelong golfer David Ross met Muhammad Ali one day on a putting green: “His limousine pulls up, and . . . he said to me, ‘I’ve never picked up a golf club before,’ and he reached out and got my putter.”

By the 1970s, black people could comfortably play at many courses. As the demographics of the city changed around it, Langston did, too. Today newcomers—often white and in their twenties—play just as often as the old-timers. The course, however, is again in shambles. The National Park Service says it will open up operations to bidders this year and will strike a new contract by October 2020. But a similar plan to renovate was under way two years ago and ended abruptly. Longtimers hope the limbo will soon be in the past—and that after 80-some years, the course conditions will finally befit its loyal players.

John Mercer Langston, Howard University law professor and namesake of the golf course.